Ankle Sprains

However, a significant minority will continue to be troubled by ongoing symptoms, including pain, swelling, stiffness and/or instability. To understand why, it is important to consider the anatomy and structures that can be damaged in an “ankle sprain”.

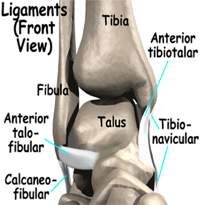

The ankle comprises of the tibia, fibula and talus bones, which are arranged in a mortise, which is held together by a capsule and ligaments.

The lateral ligaments, anterior talofibular, calcaneofibula and posterior talofibular ligaments restrict inversion (inward) movement, the most common direction for a sprain. The most forward of these ligaments, the anterior talofibular (ATF), is the most commonly injured ankle ligament in sport (when the foot points and inverts).

The medial ligament (deltoid) is strong and is far less likely to tear, however acute eversion and/or external rotation can do this. Acute eversion may result when a player lands on an opponent’s foot, from a jump (such as in basketball).

The ligament complex holding the tibia and fibula together, called syndesmosis, can be injured in a forced external rotation of the foot, such as when a rugby player is tackled on a fixed foot or with a high impact injury as when a gymnast lands from high bar.

The overall result can be a spectrum of injuries ranging from mild sprain of the anterior (front) of the ligament complex through to complete disruption and separation of the tibia and fibula. This injury is called “diastasis”, and is often accompanied by varying damage to the medial ligament and/or fibula near the knee.

In all these injuries, there is potential damage to the joint (articular) cartilage. This aspect may be overlooked initially, but can represent the most serious threat for long-term outlook. Clinically, look for focal tenderness on the dome (front of ankle) with a history of ongoing pain and swelling that is activity induced.

Common sprains of the lateral ligaments are treated with ice, compression and elevation for 24-48 hours. Most cases will not require x-ray however, early weight-bearing is encouraged followed by a functional rehabilitation program. Optimally this should be supervised by a Sports Physiotherapist.

Whilst many cases of ongoing symptoms are the result of an inadequate functional rehabilitation, some are related to a missed fracture (including talar dome lesion), persistent inflammation or associated tendon damage. These complications can be easily assessed by a Sports Doctor of Physiotherapist.

Bracing vs Taping

Many ankle sprains stretch either the ligaments on the inside or outside of the ankle. This may make the ankle hyper-mobile and reduce its dynamic stability leading to decreased muscle control.

After such an injury every effort should be made to restore normal range of movement, strength and muscular control. If the injury has been quite severe i.e. more than one week off activity, then it would be important to tape the ankle for the first 3-6 weeks post the injury.

There are many ways to tape an ankle with education and advice being available from you sports medicine practitioner. If an ankle becomes chronically unstable but does not require the full support of strapping then ankle bracing can be appropriate. There are many ankle braces on the market with some providing additional thermoplastic or hinged support on the sides. There is no perfect brace and what suits one ankle may not suit another person's ankle.

Braces with solely stretch material sup- port are often not sufficient. Braces with mouldable components and/or lace support tend to be superior in quality and stability enhancement. The physical outline of the ankle (bony vs rounded), the sport and type of foot- wear will all be factors in deciding the most effective brace.

It must be remembered that repetitive taping/ bracing may weaken the natural muscle stabilisers,. Therefore, continuous muscle strengthening and proprioception (balance) work must be undertaken.

Repetitive ankle sprains may require surgical stabilisation hence the use of effective intrinsic (muscle) and extrinsic (braces/taping) is often appropriate.

02 9231 0102

Park House Level 3, 187 Macquarie St Sydney NSW 2000

Park House Level 3

187 Macquarie St

Sydney NSW 2000

187 Macquarie St

Sydney NSW 2000